(2674 words – 10 min read) I once watched an interview with Steven Spielberg where he waxed lyrical about the notion of storyboarding and its importance. It was not only as a tool to realise his vision for himself, but also as a way to help explain to the rest of the crew exactly what was in his head.

The more I dug into this whole sphere of storyboarding, the more I found out that all of the top directors—from Cecil B. DeMille, Victor Fleming and Alfred Hitchcock, to Christopher Nolan, the Coen brothers and Martin Scorsese—all set out, in detail, the structure of their film. They showed exactly what would be in every frame, including what the camera would do, where it would start and end.

Storyboarding skill and implications

A particular skill among many talented storyboard artists is to draw to exactly the size lens that is envisaged by the director. A low-angle 25mm tracking shot with a wide depth of field (which is the amount of image in focus at any given time) would be vastly different to an 85mm long-lens shot with an extremely narrow depth of field. These shots would not only portray two totally different emotions within the scene, but give many production departments totally different information as to what to prepare for.

Benefits of storyboarding for each production department

The sound department would also know the size of the shot, and hence where the microphone booms could be placed. There is nothing worse than a boom mic drifting into the shot on every take.

Been there, seen that.

The production design team would get to know how much set would be needed to cover the scene. Or which details to llok for when doing a reccy. This in turn has major implications on the set build, post-production, scheduling, and the overall production budget.

Perth lad and now Hollywood-based Steadicam operator Andrew Rowlands is at the coalface when high profile directors are setting up their shots. He’s worked with Martin Scorsese on Gangs of New York, The Departed, among many others:

I think, in some of the big visual FX movies, everything is storyboarded. And also, they have animatics, which is a small cartoon of the movie already, so we tend to follow that pretty much for specific stunt sequences that have to be compiled over weeks or months and on different locations.

That helps us string it all together. So a Director will pretty much storyboard the movie months prior to the starting of filming. We usually have a big board up on the day, so these are the shots we are trying to get today. And they give us an idea of what the original concept was.

We don’t have to stick specifically to that, but that’s just a guide for what we’re doing. Each day, we find different problems pop up and different opportunities pop up to help move you along, or not.

But let’s step back a bit.

The Director is not (necessarily) a storyboard artist

You’ve got to ask the question: how does a director explain/describe to the storyboard artist exactly what they want, in order to enable the artist to then translate the director’s vision into their incredibly detailed version?

I am thinking that the director has to create his or her interpretation. In other words:

Present a basic, dumbed-down visual and let the artist do his/her job

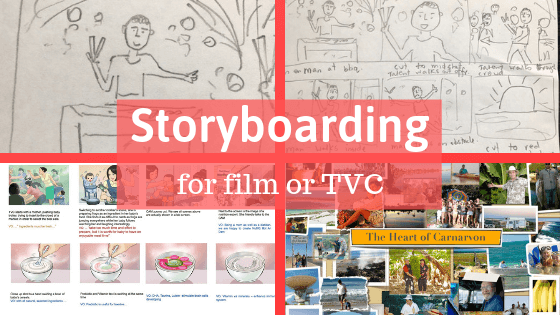

Let’s talk about a film director… me. With limited artistic hand/eye coordination, or any drawing ability for that matter. Who, after years and years of dodgy chooky scratching/freestyle sketching/wimpy drawings, still manages to draw everyone to look like pigs.

No, not chooks… pigs. Like this:

But humans with pig heads are OK too, ya’ know. It is all about spilling your head onto the page and for me it is by far the easiest way. There are other ways, using storyboard software like Toon Boom, Storyboard That, or Springboard. But really, that’s time-consuming. Well, that’s my opinion.

Storyboarding for TV Commercials: understanding the process

In the TV commercial genre, similar to the long-form variety, after the concept/script is finalized, the storyboard is integral to bringing the idea to life and illustrate all the key elements.

The process goes something like this…

Client wants to advertise. Client calls its advertising agency.

“Please come over. I want to brief you on a product or initiative we want to sell to the market.”

Agency account service director and assistant meet with the client—usually, the company marketing director—and gets briefed. When taking notes, the agency account service takes into consideration the type of product, the time of year the ad is airing, the target audience, and, most importantly, the budget, before deciding on what media strategy to recommend the client.

The budget, however, will determine what form the media will take.

Will it be a print ad in the newspaper? A billboard on key sites around the area that their target market frequents? A viral web ad? Do they buy the naming rights to an event? Is it a radio campaign or a TV commercial?

1. Key aspects to consider: budget, target and objective

The TV commercial, due to its reach and impact, is by far the most influential. And, hence, the most expensive. It is not just the making of the ad that costs the bucks. It’s the media budget to air the commercial that chews up most of the money. In days gone by when a TV commercial was the main thrust of a campaign of the client’s total budget, approximately 20-30% was allocated to production, with the balance going towards buying the media and other related campaign costs. There are just s many options now so it will really depend on the total spread of the media: TV, radio, billboard, viral, web, smart phone, mobile….onwards.

So the account service returns to the agency and prepares a brief for the agency’s creative team. One of the key points to the brief is what the client wants the viewer to do as a result of seeing the ad. The brief writers would have considered the product’s target market—e.g. male 25-50-year-old blue-collar workers, or professional working female mums 25-39, or teenage males/females age 12-19. This will affect the what/where/how. For example, is it high-brow humour, or is it factual with a price and a call to action?

I am trying to keep this simple in order to get to the bit where the storyboard comes in!

The creative team gets the grief.

Generally, the team consists of an art director/writer duo that works together regularly, has worked on the account, has extensive knowledge of the client’s history and, most importantly, has a feel for their brand and where it sits in the market. Let’s assume at this point that they are briefed on a TV commercial.

2.Creating concepts and storyboards for approval

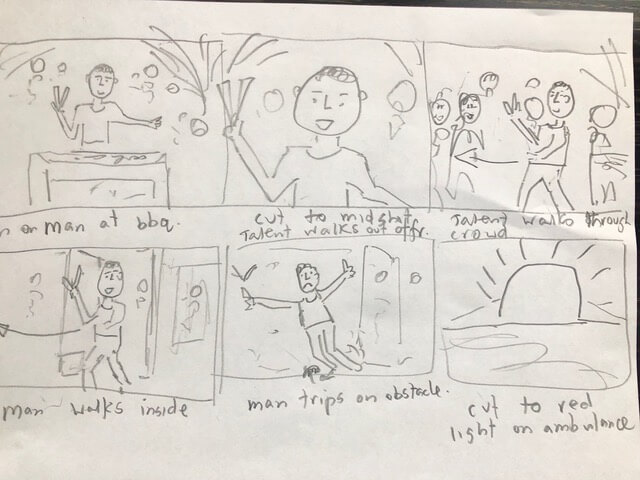

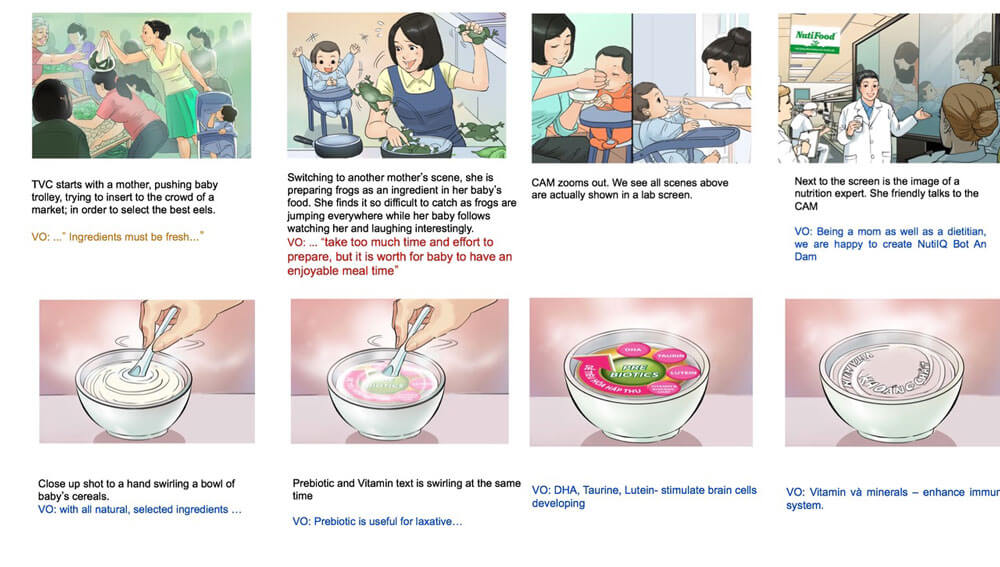

They come up with a number of concepts. Some are solid, innovative ideas, some will never see the light of day. In order to sell the ideas to the clients, all concepts need to be clearly scripted in audio-visual (AV) form. This is a two-column format that displays the audio in one column, while the other column contains a visual description of what will be seen while the respective words are uttered or sounds are heard. Then comes the storyboard.

To assume that the client is going to be able to visualize the script concept is a long shot. So, an agency artist draws up, in full colour, a storyboard that shows a broad overview of the commercial, with accompanying words underneath that describe the scene, along with whatever audio is to be heard or spoken in that scene.

The client considers, pondering the idea options. Amongst the many will be a couple of gems of ideas that the client likes. Those concepts will answer much of the brief, sell the client’s product clearly and efficiently, and aim directly to its target market. But the client may make comments about the ideas that require changes. With a number of tweaks and adjustments (this can take an age), and after many updates and re-writes, the final approved script is created.

3.Testing storyboards in research

The client, however, may retain an interest in two concepts, not one. He’s keeping his options open, even though only one concept will get made. This is going to cost the client, to have both concepts tested in research.

4. Mood board

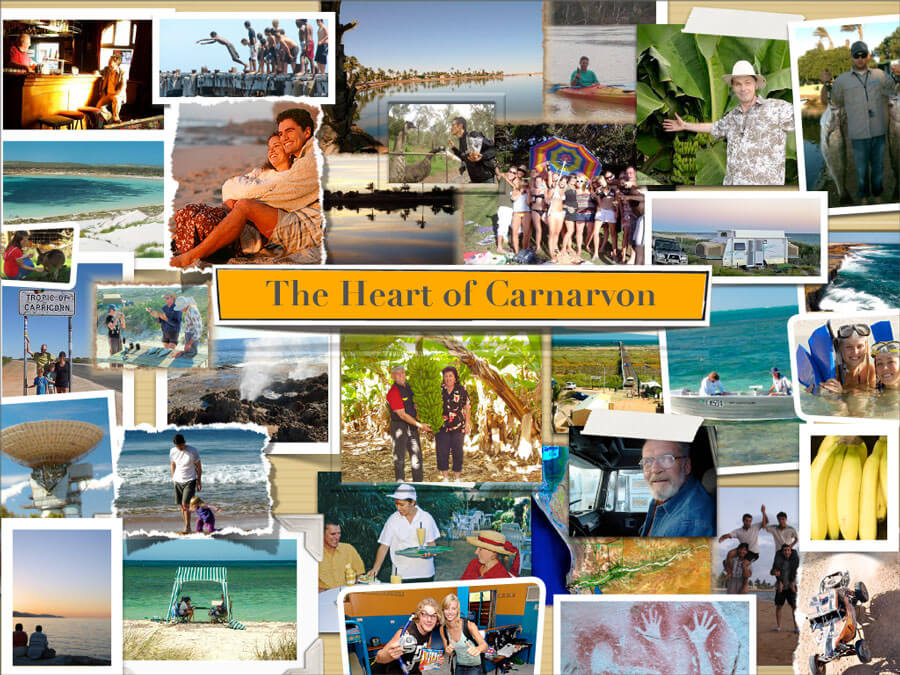

Now in order to maintain momentum, a mood board may accompany the concepts to help explain the concept better. This is a series of images that show the client the sorts of emotion that can be expected from the words. The mood board may even be a steal-o-matic: a collage of moving images stolen from other similar commercials, and made into a mock commercial with the client’s logo and call to action, positioning statement or address at the end of it.

At this point, the agency sends the project out to commercial production companies—generally three—to get their quotes. These companies have been selected because they have produced work for the agency of consistent quality, or because the company represents a director whose showreel reflects the style of commercial that they seek.

5. The Director’s input on the agency Storyboard

It is at this point that the director receives the agency storyboard, and is asked to create a treatment based on their board.

The agency is seeking a more polished interpretation of their story, one that further brings their concept to life, and gives it vitality and strength. They are seeking guidance in the talent selection and overall direction, plus a keen eye for some interesting camera angles.

VERY IMPORTANT: What NOT to do as a TVC director

What they are NOT wanting is a director who tosses their idea out and proposes a new concept. That is suicide. Trust me: it happens, and it only ends in no future jobs.

Therefore, in order for you to provide the agency and client with a credible treatment and quote, you need to make sure that you understand the board. Here, a phone hook-up with the agency creatives is a great way not only to get all of the info that you need from the creators, but, crucially, to establish a trusting rapport.

Things you need to understand fully as a director:

- Who is the target market? Yes, I know that I mentioned this earlier, but that was when the agency was getting the brief from the client. You are, at the moment, creating a picture of this brand, so who will actually buy the product is pretty important.

- Is there any other supportive media advertising planned, like radio or billboards?

- Is there any history to this product (have there been commercials produced for this product before)?

- Also, is there any existing music or “themes”?

- Is the voice-over male or female?

- What is the creative’s interpretation of the agency board? There may be another way of looking at the creative approach, so this conversation can help you to be quite clear about what it is that they mean.

6. The film director prepares a storyboard treatment

Once armed with all this info, the director proceeds to construct a treatment. In this treatment, the director outlines in detail how he or she intends to film this concept. The treatment needs to:

- Offer a clear understanding of the product, along with

- An indication of shooting style: will the camera be hand-held, the view from a third person, all film on the long end of the lens, filmed at a particular time of day?

- Plan to show visual film-grading references, music references, create a sense of style via art department references, even offer a movie reference that shows a graphic treatment of acting style genre.

This will all help to paint a clear picture of the emotional take-away for the viewer.

Example of treatment

I remember pitching on a job once where the agency was searching for a way to integrate the graphics into the commercial. So, in my treatment, I set up a link to the film trailer of The Panic Room starring Jodie Foster, where, in the opening titles, these bold graphics float between buildings and react to the shadows in the scene. It helped me to win the job. I never watched the movie, just the trailer. That was enough to freak me out.

7. The Director’s storyboard as the final reference for production

A director refers constantly to the agency storyboard. But this board is a concept board, not a director’s shooting board. It has ticked the product, marketing and emotional boxes for the client but no detailed thought has been given by the agency to the framing, flow, or feeling of the TV commercial.

That’s your job.

So it is vital not to get consumed by the agency’s board. There is a story, a product, an emotional tag, a call to action. There are exceptions to this where, within an agency, there is a talented storyboard artist who understands framing and timing and the subtlety of expression; this helps enormously in communicating the idea to all stakeholders moving forward. It becomes a more realistic reference for the production company.

However, invariably, the director’s storyboard will eventually replace the agency board as the key creative reference.

The general importance of storyboarding

Here’s what director Simon McQuoid says about the importance of storyboarding.

They’re incredibly crucial. Again, they’re the thing that communicates to crew, to everyone on the job, not just the agency, but anyone involved in it, and tells them what we’re doing. Unless you get it down on paper, you’re not really sure what you’re doing.

Knowing how to use them

They are affected by your style of work. For example, I just did a job that required a certain amount of informal observing of life, and you can’t predict that. So, for that style of work, I had a shooting board that was the basic framework, but I knew that, in and around, I’d be picking a lot of different little pieces that would add spontaneity, life, and a realness that you can’t always control. A lot of those shots got into the spot, but people didn’t even know I was shooting them. When they saw them, they said, “Oh, that’s fantastic.”

Now, if I’d said to someone on a board in a pre-pro meeting that this was going to be a shot out of an old ute looking at a guy riding his bike, and that we wouldn’t see his face but it would look amazing and beautiful, they’d have looked at me and said, “How’s that going to look beautiful?” But it was one of the shots that made it in: there’s something beautiful about how the guy rides, just something about it, but you can’t possibly predetermine it.

Helping to guide the whole production team

A lot of things, however, you can, and you need to, because in very filmic, narrative pieces that have more traditional structure to them, those things are critical. The framing, the lens choice: all of those things add up to so much so, if you’re not thinking about them beforehand, you will miss an opportunity.

Some of the spots I’ve done, you can look at the storyboard and it’s exactly the same; on others, things are less so, because of their style, but still you’ve gotta have the storyboard when you’re on the tech scout because everyone will look at the board and say, “OK, I know what I’m doing.” Then you’ve disseminated the information correctly.

Conclusion

- The most effective way of getting your shots blocked and documented is to create a storyboard. If you can’t draw, that’s ok. Neither can I. :-/

- But very rough sketches or chooky scratchings can go a long way to bringing your story to life for a proper artist, who can then pick up where you left off.

- No matter what you are planning on filming, may I recommend a storyboard.